Avian Intelligence.

Bird News Items

1. Let’s start with a really interesting article from DeepMind - Alphabet’s (groundbreaking) AI group: The planet’s biosphere is the sum of its plants, animals, fungi, and other organisms. Every day, we depend on it for our survival – the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the food we eat are all produced by Earth’s ecosystems. As increasing demand for land and resources puts pressure on these ecosystems and their species, artificial intelligence (AI) can be a transformative tool to help protect them. It can make it easier for governments, companies and conservation groups to collect field data, integrate that data into new insights, and translate those insights into action. And it can inform better plans and monitor the success of those plans when put into practice. This week Deepmind announced new biosphere research predicting the risk of deforestation, a new project to map the ranges of Earth’s species, and the latest updates on our bioacoustics model Perch. (via Deepmind)

* Much of the early days on AI are captured in a great book, Genius Makers, by Cade Metz.

2. From BirdLife International: Powering over mudflats along Asia’s coasts, a group of Common Greenshanks (Tringa nebularia) look for a place to rest and refuel. As they make their descent, a fine mist appears in their vision. One by one they’re plucked from the sky. They’ve unknowingly caught themselves in a mist-net. These finely threaded nets hang high up in the sky between two stationary poles spread several meters apart. They camouflage themselves as a mist, giving it the name. By the time birds can see the nets, they’ve already been caught and dropped into its shallow pockets. These nets are a staple for ornithologists, who catch the birds to measure, weigh, tag and then release as part of their research, but outside of science these nets often have a more sinister use. (via BirdLife)

3. Berkeley neuroscientists looking at “chatty” zebra finches: When a bird spots a predator and emits an alarm call, do its neighbors think “predator” and then react? Or do they automatically freeze or fly away because that’s what they’re wired to do? Surprisingly, biologists don’t know the answer to that question, even in cases where animals clearly exhibit different behaviors when they hear different alarm calls. Vervet monkeys, for example, look down in response to a snake call and look up in response to an eagle call. But are the animals really “picturing” a snake or an eagle? New research from neuroscientists at the University of California, Berkeley, suggests that the answer is yes, at least for zebra finches. (via U.C. Berkeley)

PFF (Pictures from Friends): By John Fitzpatrick, Grey Crowned Cranes,- Kenya.

4. We like to report on rare (or vagrant) birds, and many assume they’ve lost their way. Now PhysOrg highlights a study asking are they lost or actually leading: On a 2009 hike in the Huachuca Mountains of southeastern Arizona, a group of birders heard an otherworldly, ethereal bird song floating, flute-like, through the canyon. The hikers identified the singer as a brown-backed solitaire, recognizing immediately that the bird was very far from home. The brown-backed solitaire spends its life in the mountain forests of Mexico and Central America—what was it doing in Arizona? “I had recordings of some thrush species from Mexico. When I played the first one, which happened to be a brown-backed solitaire, it was a perfect match.” Then a teenager, Van Doren helped document the first accepted occurrence of the species in the United States, earning him his first scholarly publication. Now, Van Doren is an ornithologist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and he’s still interested in vagrants: birds that show up outside their normal range or migratory route. (via Phys Org)

5. Looking to/at birds for the state of the Bay: A new website, the San Francisco Bay State of the Birds, created by the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture and Point Blue Conservation Science, provides scientists, policymakers, and the public with an up-to-date look at which Bay Area bird populations are thriving and which are declining, and what that says about the health of San Francisco Bay’s wetlands and waters. The findings suggest that the populations of Bay Area marsh birds and wetland ducks are doing well, shorebirds and diving ducks are declining, indicating that some habitats are rebounding from “rapidly evolving climate change and biodiversity challenges,” according to the project researchers, while others still need conservation attention. (via KQED News)

6. Are birds the real architects of new ecosystems: When Surtsey erupted from the sea in 1963, it became a living experiment in how life begins anew. Decades later, scientists discovered that the plants colonizing this young island weren’t carried by the wind or floating on ocean currents, but delivered by birds — gulls, geese, and shorebirds serving as winged gardeners. Their findings overturn long-held beliefs about seed dispersal and reveal how deeply interconnected life truly is. (via Science Daily)

7. From Audubon, an update on what science tells us about birds and wind turbines: The 2025 U.S. State of the Birds report revealed that birds are sufferingrapid population declines across the United States from impacts like habitat loss. Audubon’s science shows that two-thirds of North American bird species are at risk of extinction unless we take bold action to cut pollution and slow the rise in global temperatures. Increasingly extreme weather conditions and shifting seasons are already altering ecosystems and threatening species’ survival. When done responsibly, developing more land-based wind energy can help protect birds from these escalating threats. As demand for energy continues to grow, it is essential that we plan thoughtfully for how to meet those needs. (via Audubon)

PFF (Pictures from Friends): By John Fitzpatrick, Eastern Chanting-Goshawk, - Kenya.

8. Key spot for migrating raptors in Europe: No self-professed bird-lover should ever tire of ‘vismigging’, or watching avian migrations in action. This biannual event occurs when huge numbers of migratory birds follow established flyways to their breeding areas in spring, before returning along the same routes later in the year to overwinter. There are three main flyways, or superhighways in the sky, around the globe. Birds move between North and South America along the Americas flyway; the East Asia and Australasia flyway stretches from Alaska to Russia’s Taimyr Peninsula in the north, and to Australia and New Zealand in the south; while the African-Eurasian flyway is the route of choice between Africa and Europe or West Asia. (via Discover Wildlife)

9. Speaking of migrating raptors: Fun fact - The “River of Raptors” in Veracruz, Mexico, has recorded more than 4.5 million raptors annually passing overhead, with single day records north of 500,000! (Source: perplexity.ai)

10. Grim Avian flu news - H5N1 decimating the southern elephant seal population. Is it the “tip of the iceberg” of bird flu’s full impact on the world’s seals and sea lions - and on wider ocean life: At up to 5.8 metres (19ft) in length and weighing as much as 3,700kg (8,157lb), southern elephant seals are the world’s largest seal species. They spend most of their time alone, foraging at sea. But once a year, thousands gather to breed along the Patagonian coast of Argentina in a noisy, boisterous gathering of giants. Julieta Campagna, a marine biologist with the non-profit World Conservation Society (WCS), grew up listening to the breeding season’s calls: the gruff rhythmic sounds of fighting between males and the squeaky cries of hungry pups calling their mothers. In October 2023, however, she was met with silence. In 2023, Campagna and other researchers discovered hundreds of dead adults and newborn seals scattered on the Patagonian beaches of Peninsula Valdés. “I was petrified,” recalls Campagna. “We saw hundreds of dead pups being eaten by seagulls. It was a horrible scene to witness.” The culprit was a deadly strain of bird flu, known as H5N1.

11. Natural oil seepage at it again in CA: A Los Angeles bird rescue center is asking beachgoers to be on the lookout for beached, oiled birds, as a suspected natural oil seepage in the Ventura area is primarily affecting a specific waterbird. So far, the International Bird Rescue center in San Pedro has taken in 97 oiled birds in the last three days from the Ventura, Santa Barbara area, where natural oil seepage is common, the center’s CEO said.The affected birds, Western Grebes, have black and white feathers, long, pointy bills, and distinctive red eyes. (via CBS News)

PPF (Pictures from Friends: By Walker Ellis, Barred Owl,- Charlotte, NC.

12. An “explainer” on birds and power lines: Power lines are a great place to look if you are in need of birds or shoes. It’s not unusual to see a group of small birds, or a larger bird, apparently relaxing on wires used to transfer electricity over long distances to consumers. So why do they do this, and how come they don’t get instantly turned into fried blue tit? The “why” is fairly simple to explain. While it would be fun to think that birds are simply secretly powered by electricity (see how easy it is to make up aconspiracy theory?) the truth is that power lines offer an appealing perch from which birds canview their surroundings for potential predators or prey. Up there, their views are unobscured by the foliage of trees. As for why they don’t get electrocuted, the answer is muddied by the fact that many of them do. (via IFL Science)

13. The Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallapavo) running “wild” in Detroit (Boston, too!). Robots to the rescue: Emboldened wild turkeys have become such a nuisance in some Metro Detroit communities that a high-tech solution is underway to help. It looks like a dog and barks like a dog, but isn’t a dog. It’s a robot designed to stop turkeys from terrorizing University of Michigan students. Rather, it will be. The robot is still under development by UM mechanical engineering students working with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources to build an artificial intelligence-driven robot designed to move turkeys away from people on campus. (via The Detroit News)

14. What it takes - in this case, to be a “Bird City”: Decatur is Georgia’s first certified “Bird City.” The designation, similar to the “Tree City” and “Bee City” labels, which have been around longer in Georgia, signifies the city is doing education and outreach and working to protect or improve habitat for birds. A big part of Decatur’s bid was Legacy Park, a relatively new park that the city acquired in 2017. Decatur has worked with partners like Trees Atlanta to pull invasive weeds out of the woods and plant native trees and shrubs. “The wetlands, I think that’s one reason why this is a really great place for birds and for migrating birds,” she said. “They act as resting places. They provide food. They provide shelter.” (via WABE PBS)

15. Yikes! More on bird-eating bats: After decades of mystery, scientists have finally proven that Europe’s largest bat, the greater noctule, hunts and eats small songbirds mid-air—more than a kilometer above ground. Using tiny biologgers strapped to bats, researchers recorded astonishing dives and mid-flight chewing sounds confirming bird predation long suspected but never observed. (via Science Daily)

By Hap Ellis, Northern Harrier - Parker River NWR - Newburyport, MA.

16. Grunting tennis players are way more annoying than woodpeckers: Woodpeckers really know how to punch above their weight. The woodlandbirds can attack a tree at about15 miles per hour with their powerful beaks. To achieve this, woodpeckers essentially turn themselves into hammers, by bracing their head, neck, abdomen, and tail muscles to hold their bodies completely rigid when they pound into wood. While each impact is driven with their hip flexor and front neck muscles, biologists have learned that there is a more breathy force at play here. Like tennis stars grunting to sync and stabilize their core and whack a ball, woodpeckers also synchronize their breathing with their movement when they strike wood. The findings are detailed in a study published today in the Journal of Experimental Biology. (via Popular Science)

17. Finally, please remove your eBird sighting! Of what? Well, in NYC there is an “owl code”. And not everyone is happy about it. A fun read: We followed the Owl Whisperer around the gun battery toward a grove of pitch pines, where he had seen the saw-whet owl. Then I heard someone ask behind me, “Where are they going?” I turned around and saw a couple I had met earlier. My heart sank. I had learned that they were getting into birding and that we lived in the same neighborhood. I wanted to tell them. I really did. I knew how exciting this could be for them. But there was an owl code in New York. Yes, an owl code. This varies by borough. Brooklyn, my home, is the strictest. (via Defector)

* Editor note: eBird’s software employs excellent protection for truly rare or endangered species to keep disturbances from photographers and birders at a minimum. But typically most owls that nest in urban areas - at least here in Boston - are a pretty hardy lot, according to folks at the Cornell Lab.

Bird Videos of the Week

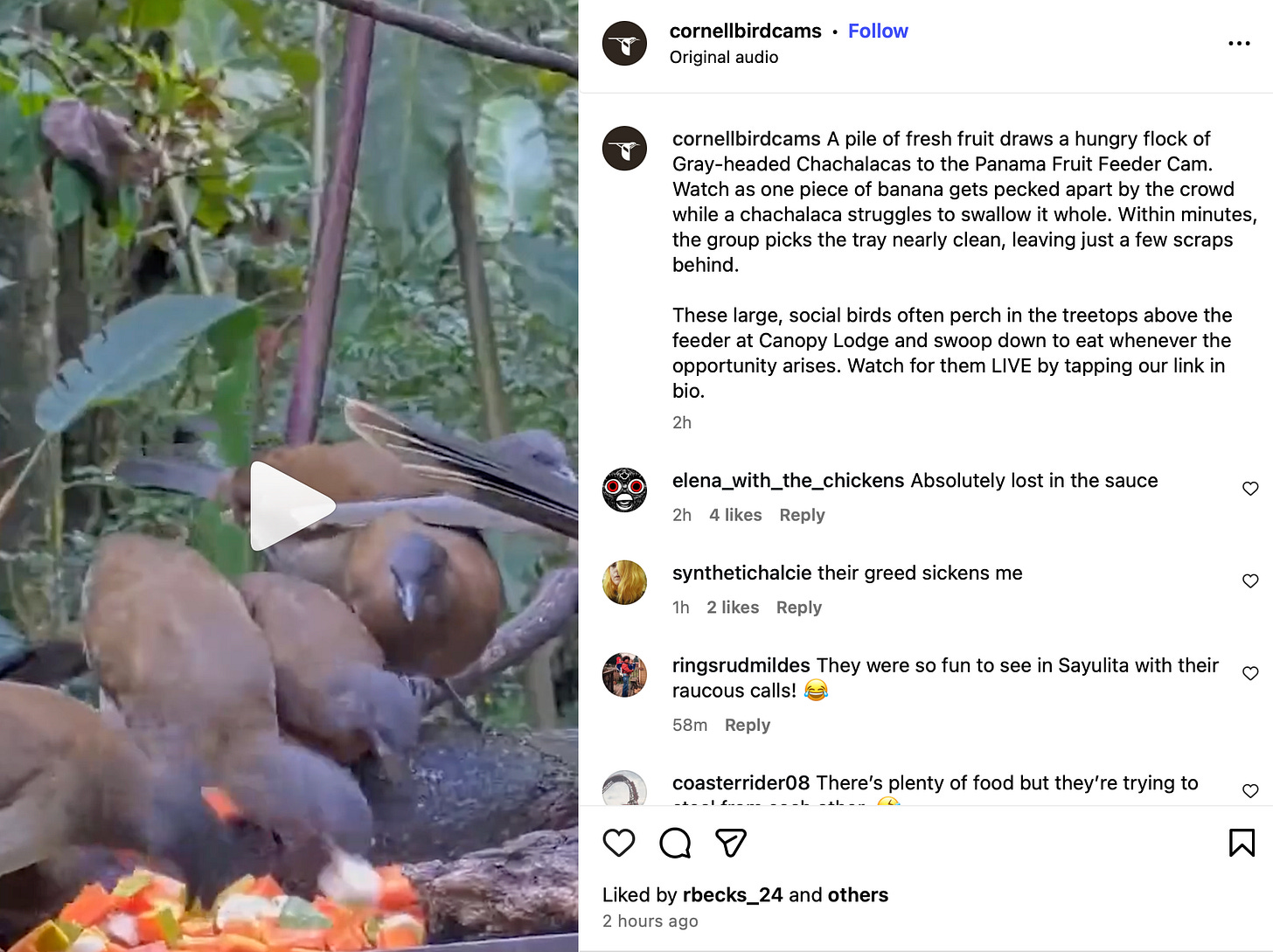

Cornell Live Bird Cam - Pile of fresh fruit draws a hungry flock of Gray-headed Chachalacas to the Panama Fruit Feeder Cam.

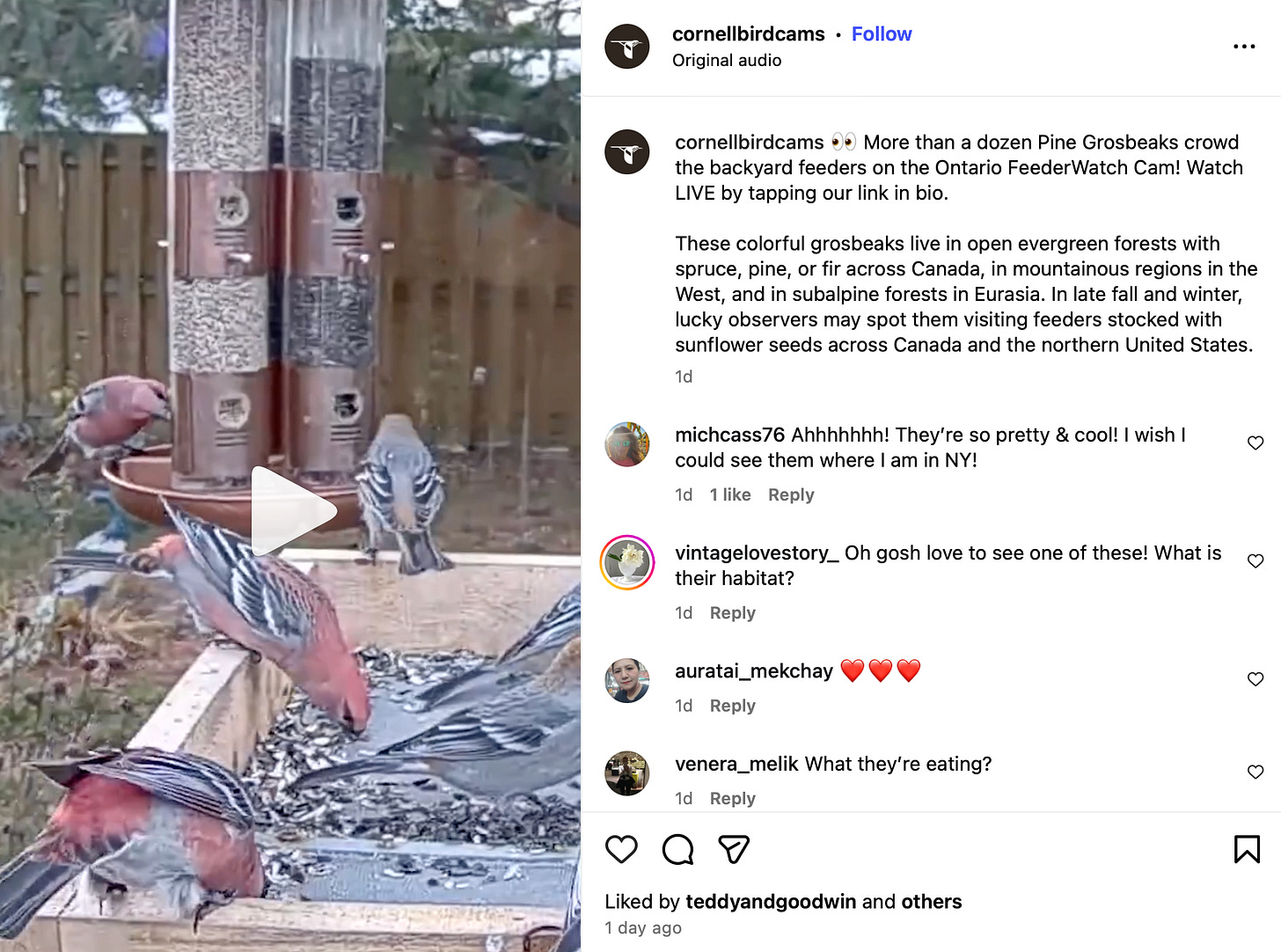

Cornell Live Bird Cam - A dozen Pine Grosbeaks.