1. Let's start with a fascinating piece in Nature on how scientists are using AI to decode the sounds of whales, elephants and crows: The great progress seen in AI systems’ understanding, translation and generation of human language is mainly due to the vast quantity of examples available, the meanings of which are already known, says David Gruber, a marine microbiologist who founded the scientific and conservation project the Cetacean Translation Initiative (CETI). “I think it’s a big assumption to assume that we could take all that technology and just turn it towards another species and have it somehow learn and start translating,” he says. The CETI project focuses on sperm whales and has become a sponsor of Gero’s research. But even before CETI, Gero had spent thousands of hours in the waters of the Caribbean leading the Dominica Sperm Whale Project, in which he and his colleagues collected data on more than 30 whale families that live near the island.

2. Last week we highlighted a NYT story on "the Blob" and its impact on birds in the Farallon Islands off southern coast of California. This week The Washington Post reports on what researchers think was the single biggest "die-off" of any bird species ever recorded, this time in Alaskan waters: When Heather Renner and her colleagues began noticing thousands of common murres washing up on Alaskan beaches nearly a decade ago, they knew something was terribly wrong. It would take years of study to confirm they had witnessed the largest die-off of any bird species ever recorded in the modern era, according to new research published in the journal Science on Thursday. (via The Washington Post)

By Hap Ellis, Volcan de Fuego - 9.9 Miles West of Antigua, Guatemala

3. Don't mess with Emus: In the 1930s, a battle unlike any other unfolded in the Australian outback. After World War I, thousands of “soldier settlers” moved to Western Australia, attracted by government incentives to develop the land. As a result, thousands of emus—tall, flightless birds—in search of food, migrated into these newly established farms and trampled crops along the way. The government’s response was swift and unusual: dispatched soldiers armed with machine guns to eliminate more than 20,000 emus. What they expected to be a quick and decisive victory turned into a humbling and absurd episode known as the “Emu War.” But this bizarre chapter in history wasn’t just a military misstep—it revealed the emus’ critical role in Australia’s ecosystems and solidified their status as one of the country’s most iconic species. (via National Geographic)

4. Also from down under, the diminutive Purple-crowned Fairy-wren is threatened as temperatures rise: Weighing less than a 50-cent coin, it’s a tiny Aussie bird you need to have an eagle eye to see. But sadly spotting the purple-crowned fairy-wren in the wild may soon be impossible, because a major change in the weather looks set to wipe it out. The warning comes after a collaboration between World Wide Fund for Nature-Australia (WWF) and Deakin University examined how a rise in temperature by two degrees above preindustrial levels would impact the birds across the country's north. World average temperatures have already increased by around 1.5 degrees, and at this level of warming the bird will likely retain 61 per cent of its habitat. But if the temperature rises by a further 0.5 degrees that figure is set to flip, and it will lose 62 per cent. (via Yahoo! News)

5. Celebrating the return of the Sandhills with "one of the quirkiest events in Texas": Some of Galveston's most elegant Winter Texans are beginning to arrive on the island and this weekend brings several activities in their honor. As a part of their winter migration, Sandhill Cranes make a stop on Galveston Island and this weekend birding enthusiasts will welcome them with the annual "Holiday with the Cranes." According to Visit Galveston, the weekend has been named “one of the quirkiest events in Texas” by the New York Times. (via Houston Chronicle)

6. A tradition unlike any other - no, not The Masters. The Christmas Bird Count! It's that time of year and Southwest Audubon offers an early (and helpful) review: I left the house early, with just my young son in tow. The year was 2013, well before the pandemic, and coffee was brewing for the relatives still a-snooze in a home strewn with toys and wrapping paper. It felt good to escape the holiday cocoon for an outdoor adventure. For my son and I, even 10 years later, the Christmas Bird Count remains a greatly anticipated break from the holiday frenzy and a precious time to reconnect: both with each other and with nature. Although some folks hear the words “Christmas Bird Count” and visualize an arduous dawn to dusk marathon, such is not the case. Although there are some die-hard birders up early to count owls and out late to hike that extra two miles, most participants are like me, fitting the event into a packed holiday schedule and finding it a peaceful and meaningful break. (via Southwest Audubon)

* Click here for Oregon Live's take on CBC

By Hap Ellis, (wintering) Western Kingbird - Lake Atitlan area, Guatemala

7. Data cubes - Phys Org covers a Princeton University study by evolutionary biologists who used hyperspectral imaging to investigate bird plumage color: Evolutionary biologists at Princeton University recently used hyperspectral imaging, a state-of-the-art tool that measures detailed spectral information at each pixel in an image, to investigate avian plumage color. Hyperspectral imaging works by separating the light spectrum into a series of narrow bands, each corresponding to a small range of wavelengths. Essentially, an image is taken in each of these narrow bands, generating a stack of images (or a "data-cube") that includes both spatial and spectral information. Each pixel in the data-cube contains detailed information about the wavelengths of light reflected. (via Phys Org)

8. Cash for birds (again!) - more from Audubon on its Conservation Ranching program: “Since 2017 Audubon’s Conservation Ranching program has zeroed in on livestock as a lifeline to birds across some 2.8 million acres and counting. Participants who manage habitat in bird-friendly fashion can earn a seal that helps market their products to consumers. Dave Haubein, whose Missouri operation was the first to be certified, says regenerative grazing also yields richer beef from healthier animals. “It’s transformed this ranch,” he says. (via Audubon)

9. One cool bird - Bird Life International highlights the Arctic Skua (aka, Parasitic Jaeger here in N.A.): Arctic Jaegers, also called Arctic skuas, are known to be acrobatic flyers. At sea, they can be seen flying low and fast over the waves in impressive pursuit of prey. But these forceful sky artists have two faces. At their breeding grounds on land, they are very aggressive – dive-bombing anyone who gets close to their nests. When the breeding ends, Arctic Jaegers embark on spectacular migrations, some wintering in the Canary Current off West Africa, while others travel further into the southern hemisphere, wintering off south-west Africa or south-east South America, and covering distances of over 10,000 km. (via BirdLife)

By Hap Ellis, (wintering) Orchard Oriole - Antigua, Guatemala.

10. And the Chinook Observer has a short take on one of our favorite shorebirds - The American Golden-Plover: Cape Disappointment seems to be a happy place for birds that have blown in on our stormy days. The burrowing owl is still hiding out in the rocks on the jetty. The latest avian to take advantage of Cape D is an American golden-plover. It has been seen for several days. It should say for a while as long as it is finding enough food for survival. The plover appears to be hanging out in the fields between Waikiki Beach and the ocean beach located next to the jetty. This is not unusual since some golden plovers frequent the prairies and plowed fields. The field where the bird is being observed is not plowed but it is the type of habitat often frequented by this plover. Thus, it is easy to see why the American golden-plover can continue its stay at Cape D. (via The Chinook Observer)

11. Fun musings on birding from the kitchen window: My last visit to the Thinking Chair occurred on Oct. 20 — a bright, sunny day. There had been a frost during the night, which produced some interesting effects on the remaining leaves down in the meadow. The following Saturday was cloudy and very windy and on Sunday the temperature was 32 F, which convinced me to throw in the towel. Migration was over and the few remaining birds of the meadow would surely be up at the house, so that was the end of another season at the Thinking Chair. This required a change of venue for my bird observations and the kitchen window took over as the nexus of my birding universe. I had already purchased a variety of new feeders and feeder hangers and I happily set about the process of fine-tuning everything. Which feeder would work best where? What needs to be cleared out of the way? What could be added to increase the fun and productivity? (via Berkshire Eagle)

12. And then a similar piece from the Guardian's "Country Diary": A day of incipient winter, sun bright in sharp blue sky. Hat and gloves weather. Tooting Common pond is home to ducks and geese and swans (oh my!) – what a birding friend dismissively calls “the usual rubbish”. But for a few weeks now there has been a glamorous addition, a rarity, flown in from wherever to bestow a hint of the exotic on these everyday urban surroundings. A ferruginous duck – “fudge duck” for short, the nickname felicitously combining abbreviation and a succinct description of the bird’s colour. Reports say that it’s a first-winter female “of unknown origin”. This is code for “probably escaped from a wildfowl collection but without a leg ring we can’t be certain”. Hardcore birders, valuing the truly wild above all else, might sniff at an escapee, but a bird is a bird. Besides, I have never seen a ferruginous duck, and while I wouldn’t usually make a special journey for a sighting, this is merely a short extension of my daily walk. It would be rude not to. (via The Guardian)

13. Making field work safe for all: In spring 2020, Covid-19 restrictions forced then-PhD student Murry Burgess to conduct her field research entirely alone. Driving to the rural North Carolina barn where she was studying the effects of light on Barn Swallow chicks, Burgess, who is Black, passed Confederate flags and endured suspicious glares when she stopped at a local gas station. Motivated by the sense of unease she felt as a Black PhD student checking swallow nests by herself, Burgess wanted to create a support network for the next wave of minority scientists coming up behind her. In August 2022 she and Lauren Pharr, a fellow Black grad student at N.C. State, established a nonprofit group named Field Inclusive. Over the past two years, the startup has taken off and flourished as a career-building community for grad students across the country who come from historically underrepresented groups in science. (via Living Bird Magazine)

14. Finally, do find time to watch this wonderful video by the Cornell Lab's Conservation Media team on a bird you may hear but likely will never see:

Bird Videos of the Week

Video by BBC Earth, “Playtime for Young Kea Birds”.

Cornell Live Bird Cam - Northern Albatross Nest.

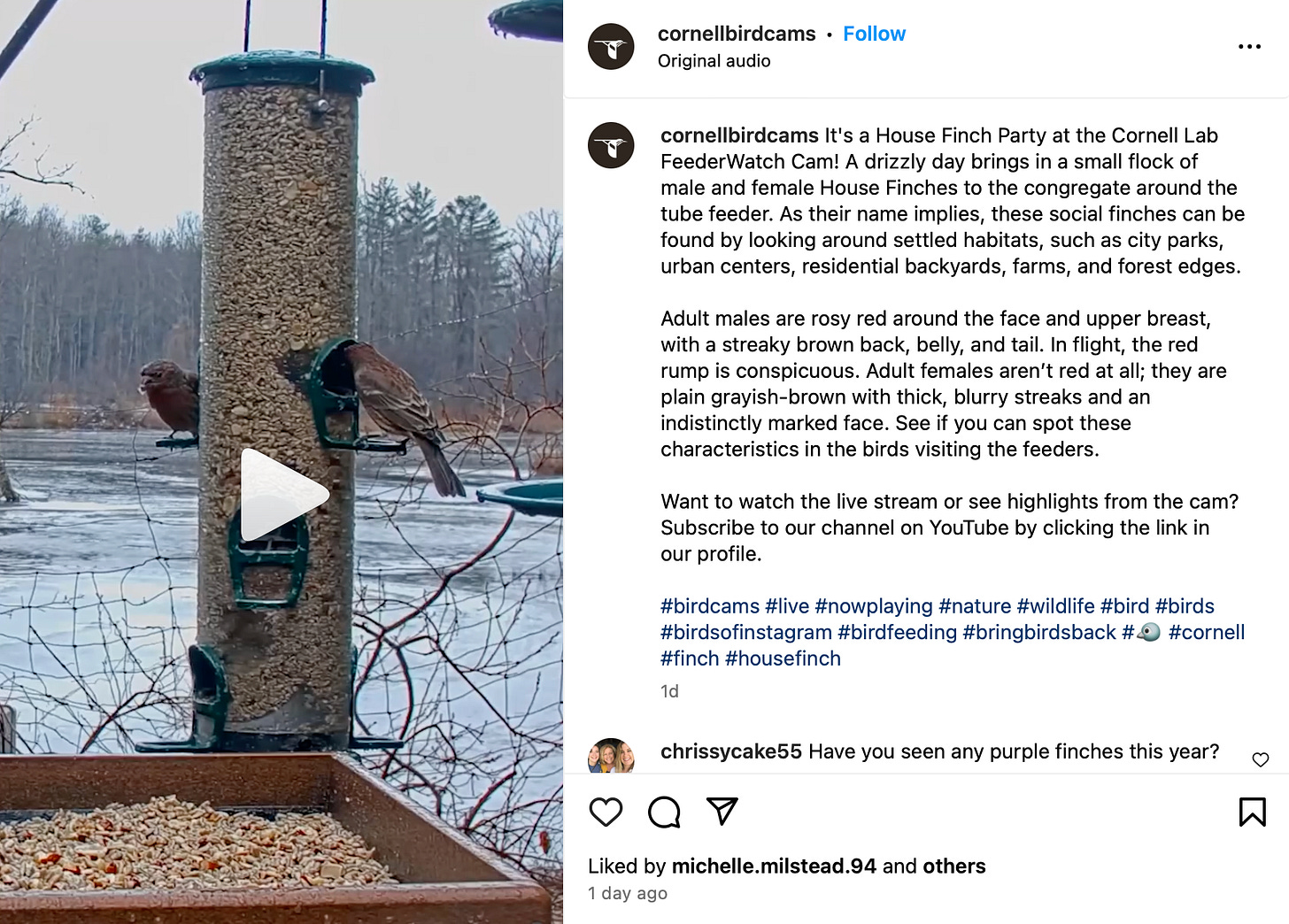

Cornell Live Bird Cam - House Finch Party.