Fright Flight.

Bird News Items

1. Let’s begin with a murder mystery – at 10,000 feet: In January 2023, scientists attached tracking devices to eight grey plovers on the coast of the Wadden Sea off the Netherlands. The hope was to learn more about the birds’ yearly migration to breeding grounds in the Arctic. And all was going well until late May, when one of the birds started acting strangely. “The first thing we noticed was a sudden change in direction,” said Michiel Boom, a migration ecologist at the University of Amsterdam. While the rest of the plovers headed northwest, this bird started going southeast. In fact, the bird appeared to have rapidly descended before landing in a rock quarry — a very unusual destination for a grey plover. Soon after, the bird’s tracker stopped moving. It had become clear that this was not a bird with a confused sense of direction: The plover had met its end in the talons of a predator. (via The New York Times)

2. Who knew the Whip-poor-will is an iconic bird of American horror: In one of the most haunting scenes of Stephen King’s 1975 novel “Salem’s Lot,” a gravedigger named Mike Ryerson races to bury the coffin of a local boy named Danny Glick. As night approaches, a troubling thought overtakes Mike: Danny has been buried with his eyes open. Worse, Mike senses that Danny is looking through the closed coffin back at him. A mania overcomes Mike. Prayers run through his head – “the ways things like that will for no good reason.” Then more disturbing thoughts intrude: “Now I bring you spoiled meat and reeking flesh.” Mike leaps into the hole he’s dug and furiously shovels soil off the coffin. The reader knows what he’s going to do, but ought not to do, next: Mike will open the coffin, freeing whatever Danny has become. Enter the whip-poor-wills. Several of them, King writes, “had begun to lift their shrilling call,” the demand for violence that gives the species its name: whip-poor-will. (via The Conversation)

By Hap Ellis, Cooper’s Hawk – Millennium Park, Boston, MA.

3. Very cool program - Subletting farms to shorebirds during the Fall migration: Every July, the western sandpiper, a dun-colored, long-beaked bird, leaves the shores of Alaska and migrates south. It may fly as far as the coast of Peru, where it spends several months before making the return trip. Western sandpipers travel along the Pacific Flyway, a strip of land that stretches along the western coast of the Americas, from the Arctic down to Patagonia. The wetlands of California’s Central Valley offer sandpipers and many other species a crucial place to rest and feed along the way. At the peak of the southward-migration season, millions of birds stop there. (via The Atlantic)

4. Insects, migration and a timing mismatch – a “mounting challenge” for birds: At a glance, the male western tanager looks like a little flame, its ruby head blending seamlessly into its bright, lemon-colored body. Females are less showy, a dusty yellow. The birds spend their winters in Central America and can be found in a variety of habitats, from central Costa Rica to the deserts of southeastern Sonora, in western Mexico. In the spring, they prepare to migrate thousands of miles to the conifer forests of the Mountain West, flying through grasslands, deserts, and occasionally, suburban yards. According to a study published in early March in the journal PNAS, this kind of timing mismatch between migrants and their food sources, which is happening across North America, could have dire consequences for migratory birds’ survival. (via The Atlantic)

5. Same subject, same concern – this from the UN’s Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals: The season for bird migration has begun, with cooler weather descending upon the Northern Hemisphere, sending birds on their long journeys south to places like Singapore to escape the winter chill. Between August and March, these feathered voyagers draw plenty of attention from birdwatchers and groups campaigning for the conservation of wetland habitats where the birds stop and refuel. But a new United Nations report has highlighted a critical aspect of migratory bird survival – the decline of insects. The report has said that dwindling insect abundance, biomass and diversity are contributing to population losses among migratory birds, especially those that rely on insects as their main source of food during their migration. (via Straits Times)

6. What’s up with these huge birds? Last week a giant loon, this week a giant pigeon: If you hate pigeons, the 2,000-pound, nearly 16-foot-tall cast-aluminum rendering of the bird perched on the New York City High Line for the next 18 months might not be for you. Paris-based Colombian artist Iván Argote was commissioned by the High Line to create the sculpture, entitled “Dinosaur,” for the fourth iteration of its Plinth series. While the installation might feel “strange and funny and make you laugh,” he told Hyperallergic in an interview, it’s also meant to prod at something deeper. On a metal sign near the structure, Argote reminds the public that “even the pigeon, a New York fixture, migrated here and made the city their home.” That’s why he connects the quintessential New York bird with its human residents. “This is a city of migrants; in a way, it was built by migrants,” he added. (via Hyperallergic)

By Hap Ellis, White-throated Sparrow – Millennium Park, Boston, MA.

7. From Africa – Avian architects (spoiler - the White-browed Sparrow Weaver): From afar, the acacia trees look like they have been decorated with grass pom-poms. The birds have been busy, building shelters of straw and grass. Up close the real shape of the “pom-poms” becomes clear: grass tubes in the form of an upside down “U”, with an opening at each end. These structures are the work of white-browed sparrow weavers (Plocepasser mahali).White-browed sparrow weavers are cooperative breeders. Within a multi-generational family group, only one dominant pair will reproduce; all other birds, which are mostly kin (related), will help with the rearing of chicks. These birds do everything together: forage, defend their territory, feed new chicks – and build each of the many roosts that decorate the acacia trees they live in. The birds are found throughout central and north-central southern Africa. (via The Conversation)

8. Slackers! The White-browed Sparrow Weavers’ young males less helpful than young females around the nest: Male birds help their parents less than females because they're too busy scouting for new places to live and breed, a remarkable new study shows. The study, led by researchers at the Centre for Ecology and Conservation at the University of Exeter, examined the cooperative behavior and movement patterns of social birds called white-browed sparrow weavers, which live in the Kalahari desert. These birds live in family groups in which only a dominant pair breeds—and their grown-up offspring, particularly females, help to feed nestlings. The new study aimed to understand why in many animal societies one sex tends to invest more in helping within the family than the other. (via Phys Org)

9. Looking for fish, follow the birds: There are some old fishing maxims that people throw around a lot, and a lot of them are misunderstood. One in particular that really confuses people is, “Just follow the birds.” I’ve been riding in the boat with novice anglers as they point out every bird they see as if that will lead them to the Promised Land. While it is true that birds tell us a lot of what is going on out there, it’s important to understand what each type of bird is, how it fishes, and what it means to us as anglers. Let’s go through the most popular ones that we’ll see on our coast on any given day. (via Coastal Review)

By Hap Ellis, Great Blue Heron – Millennium Park, Boston, MA.

10. Taxonomy Update: The annual eBird Taxonomy Update is happening now! Stay tuned to this page for updates throughout the process, including an announcement when the changes are complete. Learn more about this year’s update here. “Taxonomy” refers to the classification of living organisms (as species, subspecies, families, etc.) based on their characteristics, distribution, and genetics. There are multiple taxonomies for birds around the globe. Projects at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology—including eBird, Merlin, Birds of the World, and the Macaulay Library—use the eBird/Clements Checklist of Birds of the World, or eBird/Clements Checklist for short. Our understanding of species is constantly changing. Every year, some species are “split” into two or more, while others are “lumped” from multiple species into one, as we gain a better understanding of the relationships between birds. The eBird/Clements Checklist is updated annually to reflect the latest developments in avian taxonomy. “Taxonomy Time” is an opportunity to celebrate the many scientific advances in ornithology made over the past year—some of them thanks to your eBird data! (via eBird)

11. And given our Herring Gulls are now the American Herring Gull, it’s a good time for a piece in praise of these birds: Biological conservation efforts typically gravitate toward the more charismatic species. Save the pandas is a more popular slogan than save the earthworms, and most people likely care more about protecting flowers than a rare grass or fungi. For birds, eagles and condors are beloved poster children of environmental movements. But for gulls — sometimes erroneously called “seagulls,” though they are not exclusive to the ocean — they are described as nuisances and pests, which experts say couldn’t be further from the truth. Nonetheless, public sentiment against gulls is often strong. (via Salon Magazine)

12. Birds & Hurricanes: Some shorebirds are known to use the hurricane winds to their advantage to escape. Some have been found as far as 150 miles inland after a major hurricane. The Frigatebirds and Eagles are able to “soar above the storm,” as they say. Some birds, as difficult as it might be to imagine, fly through the storm, and some of those birds don’t make it. The Eagle, for example, “uses the strong winds and updrafts to their advantage, allowing them to fly higher and further than most other birds.” So while the Eagles and the Frigatebirds soar high above the storm, the smaller birds, shorebirds and “neighborhood birds,” as I like to call them, have unique solutions when dealing with hurricanes. Luckily for them and for us, as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology explains, birds have instincts that allow them to sense an approaching storm by detecting changes in air pressure, serving as a “built-in barometer.” (via Brooklyn Eagle)

By Hap Ellis, (much maligned) European Starling – Millennium Park, Boston, MA.

13. One Cape to another – a Cape Cod birder hits Cape May in the Fall: By late October, migration is winding down on Cape Cod. Many of our summer visitors are gone, our warblers are filing out to be replaced by sparrows, and our winter waterfowl are returning from the Arctic. But just shy of 500 miles south of here, Cape May, N.J. is still enjoying peak migration. I had to see it. In the fall, as migrating landbirds travel south from their breeding grounds, they funnel down New Jersey, getting more and more concentrated until they reach Cape May Point and gather on the shores of Delaware Bay. There might be thousands of raptors and tens of thousands of warblers flying overhead near the point. (via Provincetown Independent)

14. Finally, enjoy Chris & Amy and the “transcendent power of birding”: Christian Cooper and Amy Tan came to birding from very different paths. Cooper had found refuge in birding as a child, long before the Central Park incident that brought him to national attention. For Tan, birding was a more recent discovery, prompted by a need for an outlet away from political events. For both, birding has been a powerful source of solace and community. In a free, live discussion on Thursday, June 22, Cooper, the author of the new book “Better Living Through Birding,” and Tan, author of the forthcoming book “The Backyard Bird Chronicles,” spoke about the transcendent power of birding and the challenges and the rewards of navigating a predominantly white pastime as people of color. (via The New York Times)

Bird Videos of the Week

By CBS Morning News, “The Secret Life of Pigeons”.

Cornell Live Bird Cam - Summer Tanager.

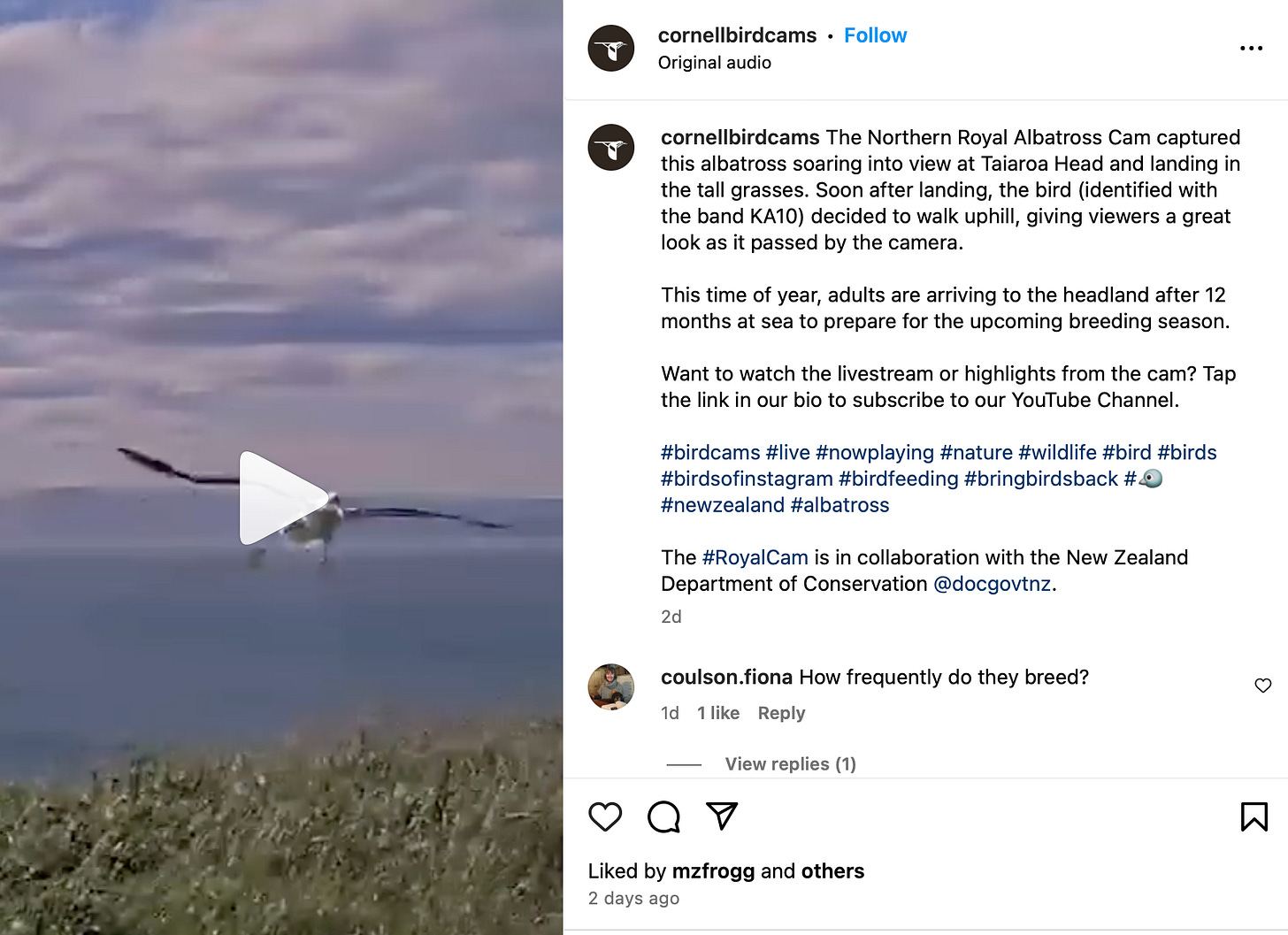

Cornell Live Bird Cam - Royal Albatross.