Snapshot Study.

Bird News Items

1. Let’s begin with “Tony”, the Bird protector, as seen through the eyes and pen of a fellow inmate: A year ago, when I was transferred to the Mark W. Stiles Unit, in Beaumont, Texas, I was surprised to see a tall and bald Latino man tending to a pair of sparrows. I’m not sure why; there were birds, turtles, fish and cats at my last facility. But I mostly tuned them out. Maybe it was just a prison mindset: I exist inside, not outside, so what’s the point of paying attention to animals? But Tony, 63, who has been incarcerated for 26 years and lives below my cell, has a different perspective. He has been the pod’s resident caretaker of a male and female bird couple living in our pod for the last three years. Their nest is 25 feet off the ground, wedged behind nonfunctional cellphone signal jammers. (via Prison Journalism Project)

2. Wait a minute! Going north, you say?: Scientists tracking young Arizona Bald Eagles found that many migrate north during summer and fall, bucking the traditional southbound pattern of most birds. Their routes rely heavily on historic stopover lakes and rivers, and often extend deep into Canada. As the eagles mature, their flights become more precise, but they also encounter significant dangers like electrocution and poisoning. These discoveries point to the need for targeted conservation of critical travel corridors. (via Science Daily & Raptor Research Foundation)

By Hap Ellis, Pileated Woodpecker - Longboat Key, FL.

3. What it takes: $400 million – divided among 19 projects - for Gulf Coast restoration: Have you been lucky enough to witness the goofiness of the Reddish Egret? The way they dance around in shallow water with their wings partially outstretched, a tactic to catch fish known as canopy feeding. I love watching these gorgeous—and eccentric—waterbirds where I live on the Gulf Coast, and I’m excited to close out the year with good news to benefit them and many other species. The Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council, one of the entities tasked with restoring the Gulf after the 2010 BP oil spill, recentlyannounced a $403 million investment to restore the Gulf Coast. This investment includes 19 projects to restore coastal habitats, improve water quality, increase community resilience, and support wildlife. Fifteen years ago, the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded, unleashing the largest environmental disaster in U.S. history. (via Audubon)

4. Maybe Rule #1 when siting large power projects is stay clear of sensitive wildlife areas? Sir Keir Starmer’s plan to build mini nuclear reactors in Britain risks being derailed by a colony of rare birds. Around 2,000 pairs of terns flock to the Cemlyn nature reserve in Anglesey, North Wales, each year, including Arctic terns, Sandwich terns and common terns. They are a protected species and their coastal breeding ground is next to where the Government is proposing three small modular reactors (SMRs), with wildlife experts concerned that construction could prompt the birds to abandon the area. There are also fears about special wetland and marine habitats in Cemlyn Bay. A nuclear industry source warned that efforts to reduce the scheme’s impact risked becoming “the next fish disco”, a reference to the £700m that was spent on fish protection measures at Hinkley Point C in Somerset. (via Telegraph)

5. An “encouraging sign” indeed: On a jagged coastline in Central California, brown pelicans gather on rock promontories, packed in like edgy commuters as they take flight to feed on a vast school of fish just offshore. The water churns in whitecaps as the big-billed birds plunge beneath the surface in search of northern anchovies, Pacific sardines and mackerel. If awkward and wobbly in appearance on land, they are graceful once airborne. The signature pouch dangling beneath the lower bill can scoop up to 3 gallons of water with every dip into the ocean — the largest pouch of any bird in the world. It is what scientists call a “feeding frenzy.” And it is an encouraging sign for a bird that has struggled in recent years with a warming ocean, inconsistent breeding patterns and toxic algae blooms in Southern California. (via AP News)

6. Chaucer described them as “ful of trecherye”; to this English country writer, they are simply “the birds of my childhood” – a short paean to the Northern Lapwing: There’s a shimmering in the sky and I can’t work it out. Driving, I can only snatch glimpses of flickering light. I pull into a lay-by near home. Now I can make out five or six broad-winged birds, flying in a loose flock. They are black and white and their motion reflects the low sun, flashing light and contrasting dark, like a disturbance in the force field. Lapwings, or “peewits” as they are known for their call, are birds of my childhood. Every spring, they nested in the same field and, in winter, flocks gathered. I loved their crest and the way their petrol-sheened plumage changed with the light, from dark green to bronze or purple. (via The Guardian)

By Hap Ellis, Crested Caracaras - Longboat Key, FL.

7. Notes from the field: A few days after I moved to Alameda, I set out on an exploratory walk of nearby Crown Beach. As I continued south on Shoreline Drive, past the bowling alley and apartments buildings and onto the sliver of a trail between a row of houses and the San Francisco Bay, my jaw actually dropped at the sight of hundreds of shorebirds—marbled godwits and western sandpipers, avocets and black-necked stilts, willets and black-bellied plovers—who were dabbling in the mudflats between the beach and Bay Farm Island bridge. A lifelong bird lover, I felt as if I had discovered gold. (via Alameda Post)

8. This 30-year “snapshot study” underscores the resiliency of the birds in the PNW: A 30-year “snapshot study” of birds in the Pacific Northwest is showing their surprising resilience in the face of climate change. The project started when Georgia Tech School of Biological Sciences Assistant Professor Benjamin Freeman found a study by Louise Waterhouse detailing birds in the mountains near Vancouver three decades ago. What followed was an ecological scavenger hunt: Freeman revisited each of the old field sites, navigating using his local knowledge and Waterhouse’s hand-drawn maps. The results were surprising: over the last three decades, most of the bird populations in the region were stable and had been increasing in abundance at higher elevations. (via Futurity)

9. From New Haven, Yale is doing its part: Yale University’s Bird-Friendly Building Initiative, a project that aims to accelerate the adoption of bird-friendly design in the built environment, has been recognized with a 2025 Excellence Award by the International Sustainable Campus Network (ISCN). By working with experts from the American Bird Conservancy’s Glass Collisions Campaign, Yale researchers focused on identifying and evaluating city, state, and federal policies and strategies that would lead to more bird-safe building design at scale beyond Yale’s campus. Insights were compiled into a 2023 report, “Building Safer Cities for Birds,” as a resource for the public, advocates, and policymakers, along with a database of bird-friendly building policies in the U.S. (via Yale Sustainability)

By Hap Ellis, Glossy Ibis - Longboat Key, FL.

10. For all of you with backyard feeders (in colder areas): By Thanksgiving, I figured my local bears were done tearing up bird feeders in my neighborhood. I tentatively put out one feeder with sunflower seeds and one with suet. Then a funny thing happened: nothing. Before the planet started heating up, it was common for birds to mob backyard feeders in late autumn. In recent years, it’s become more common to complain that they’re not mobbing feeders. Birds do not rely on feeders. They treat feeders as a supplemental food source. When there is plenty of natural food around, they may not visit feeders at all. Now that autumn lasts longer, feeders often hang limp until the first snow. Two climate surprises help explain why. (via Bangor Daily News)

11. In Boston, it is make way for ducklings; in Madison, Wisconsin, think trumpeter swans, says WPR: Along the shore of Madison’s Lake Monona, a quiet, wintry scene is interrupted by a cacophony of honks, hoots and coos. It’s migration season, and thousands of tundra and trumpeter swans — along with waterfowl of all kinds — have descended upon the city’s lakes as part of their trip south. It’s common for waterfowl like ducks, swans and geese to migrate together, en masse, said Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources conservation biologist Ryan Brady. In general, waterfowl are what Brady calls short-distance migrants that often linger later into the fall and winter. The birds’ final destination might only be as far as the southern United States, and they only travel as far as food resources force them to. (via Wisconsin Public Radio)

12. Climate studies – there are several studies, actually, along these lines: Many bird species have moved toward colder areas in the mountains of Europe as the climate has warmed over the past two decades. Sunny southern slopes attract birds to live at higher elevations than do shadier northern slopes. A new study examined 177 bird species in four large mountain ranges: the Alps, the Pyrenees, the Scandinavian Mountains, and the British Highlands. Of these species, 63% moved uphill. This uphill movement has averaged about half a meter per year in the 2000s. The study ispublished in the journal Global Ecology and Biogeography and is based on bird monitoring data from eight European countries between 2001 and 2021. (via Phys Org)

13. Breaking new ground in Nepal: Nepal has recorded the first confirmed breeding of the black-necked crane (Grus nigricollis), locally called Kalikantha Saras, in the high-altitude Limi valley of Humla district. The black-necked crane is a globally rare and near-threatened bird species in the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. The milestone observation was made along the Sakya stream plain in Namkha Rural Municipality, Humla, where a pair was seen tending a chick. “Seeing a chick with its parents is definitive proof of breeding and marks the country’s first such record. This is a moment of great significance for Nepal’s bird conservation,” said senior ornithologist Hem Sagar Baral. (via Katmandu Post)

By Hap Ellis, Caspian Tern - Longboat Key, FL.

14. Bird flu update – this item from Down Under: Bird flu, or H5N1, has touched most of the globe, but there is one spot it hasn’t reached. Researchers down under are preparing for it, but gaps in bird flu surveillance elsewhere makes it difficult. Bird flu has made its way to almost every corner of the globe. First detected in China in 1996, it’s spread across Asia and to to Europe and Africa. Catching a ride on migratory birds, it crossed the Atlantic Ocean and even turned up on Antarctica. In its wake, it has left what some describe as a global catastrophe, with mass die-offs of wild birds and marine mammals. But as NPR’s Gabrielle Emanuel reports, there is one continent that bird flu has yet to reach. It’s spring in Australia. That means lots of migratory birds are showing up on the country’s beaches. And Michelle Wille is busy trying to catch them. (via National Public Radio)

15. News from the U.N. (commitment to truth, we had to look up exactly where Bishkek is): UNDP Kyrgyzstan and the Public Foundation Nature Foundation, in partnership with the Ministry of Natural Resources, Ecology and Technical Supervision of the Kyrgyz Republic, organized a special field visit to one of the country’s most unique and internationally significant biodiversity hotspots. Just 15 kilometres from Ala-Too Square lies an Important Bird Area (IBA) that forms a vital sanctuary for migratory birds along the Central Asian Flyway. The site supports more than 200 bird species year-round, including the majestic White-tailed Eagle, whose only confirmed nesting site in Kyrgyzstan is located here. Participants also observed elegant White Egrets, colourful Kingfishers, and several other endangered and vulnerable species. In just 3–4 hours, the group identified around 40 bird species, demonstrating the extraordinary density and diversity of wildlife thriving in this compact area adjacent to the capital. (via United Nations Development Program)

16. Avian aging in (or off) Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara has a good track record of attracting rarities that come here to winter, not unlike the rich and famous humans. Our coastal climate and abundance of winter food make survival relatively easy. In the 1980s, a Grace’s warbler, a species that normally winters in Mexico, returned to a row of pine trees in Montecito for nine consecutive winters. Another famous winterer was a male hepatic tanager; beginning in 1982, he returned to Rocky Nook Park for at least twelve winters. Another male hepatic tanager has just returned to Evergreen Park in Goleta for his third winter. It will be interesting to see whether he rivals the Rocky Nook bird for longevity. Once a bird successfully winters in a given spot, the chances are that, if it survives, it will return to the same area the following winter. (via Santa Barbara Independent)

17. Finally, ‘tis the season and for those looking for last minute book ideas for your favorite birder (or bird nerd), here are a few suggestions:

For the miracle and majesty of migration: Flight of the Godwit – Tracking Epic Shorebird Migrations by Bruce Beehler

For your spouse, friend or partner who is a crazed birder: The Birding Dictionary (“A tongue-in-cheek guide for people who find themselves obsessed, against all logic and reason, with birds.”) by Rosemary Mosco

For Amy Tan fans: The Backyard Bird Chronicles, by Amy Tan

For the beauty of birds: Birds, The Art of Ornithology, by Jonathan Elphick

Bird Videos of the Week

Video by Birding Better, “The Yellow Cardinal Explained by an Ornithologist”.

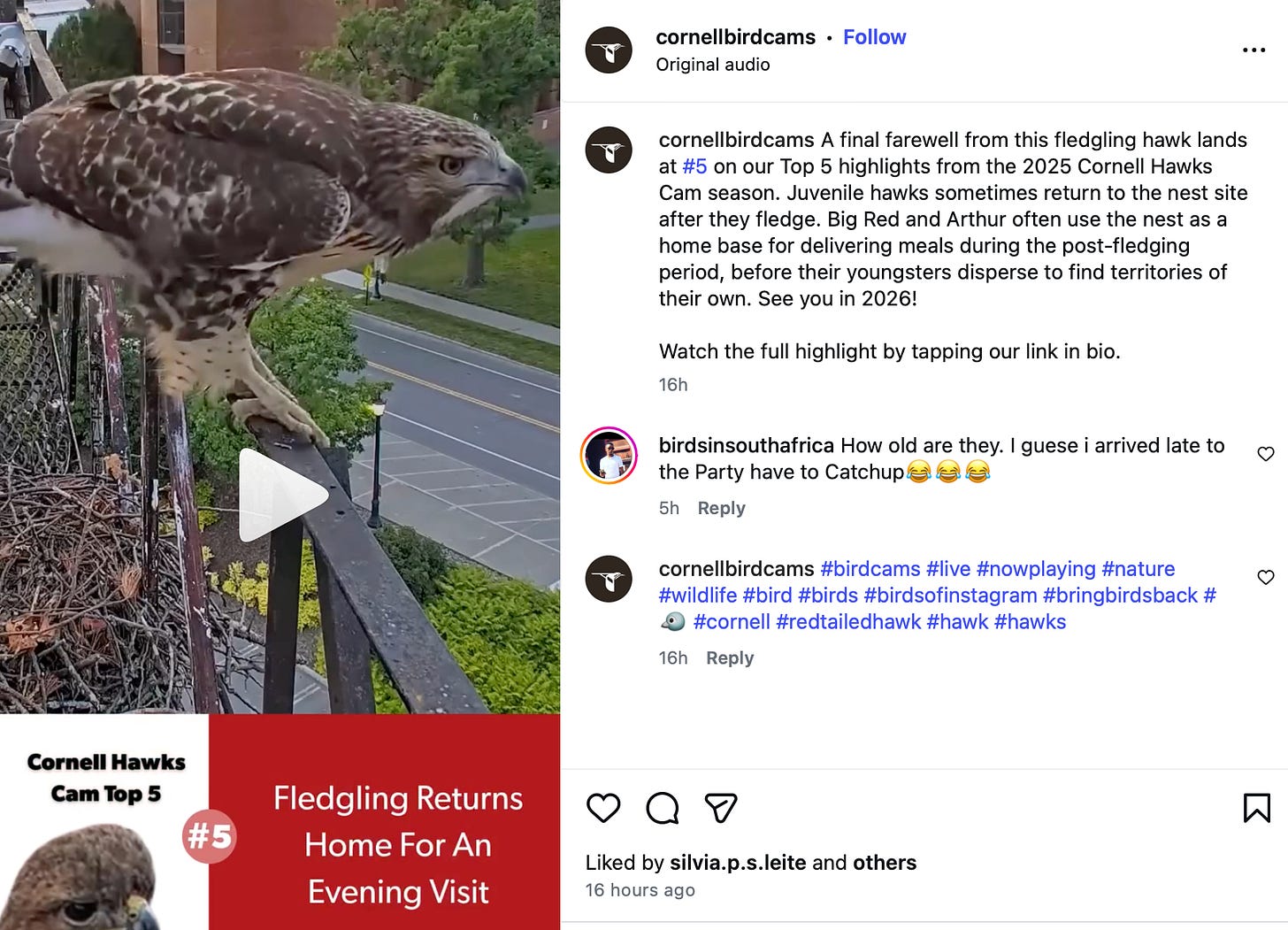

Cornell Live Bird Cam - A final farewell from this fledgling hawk lands at #5 on our Top 5 highlights from the 2025 Cornell Hawks Cam

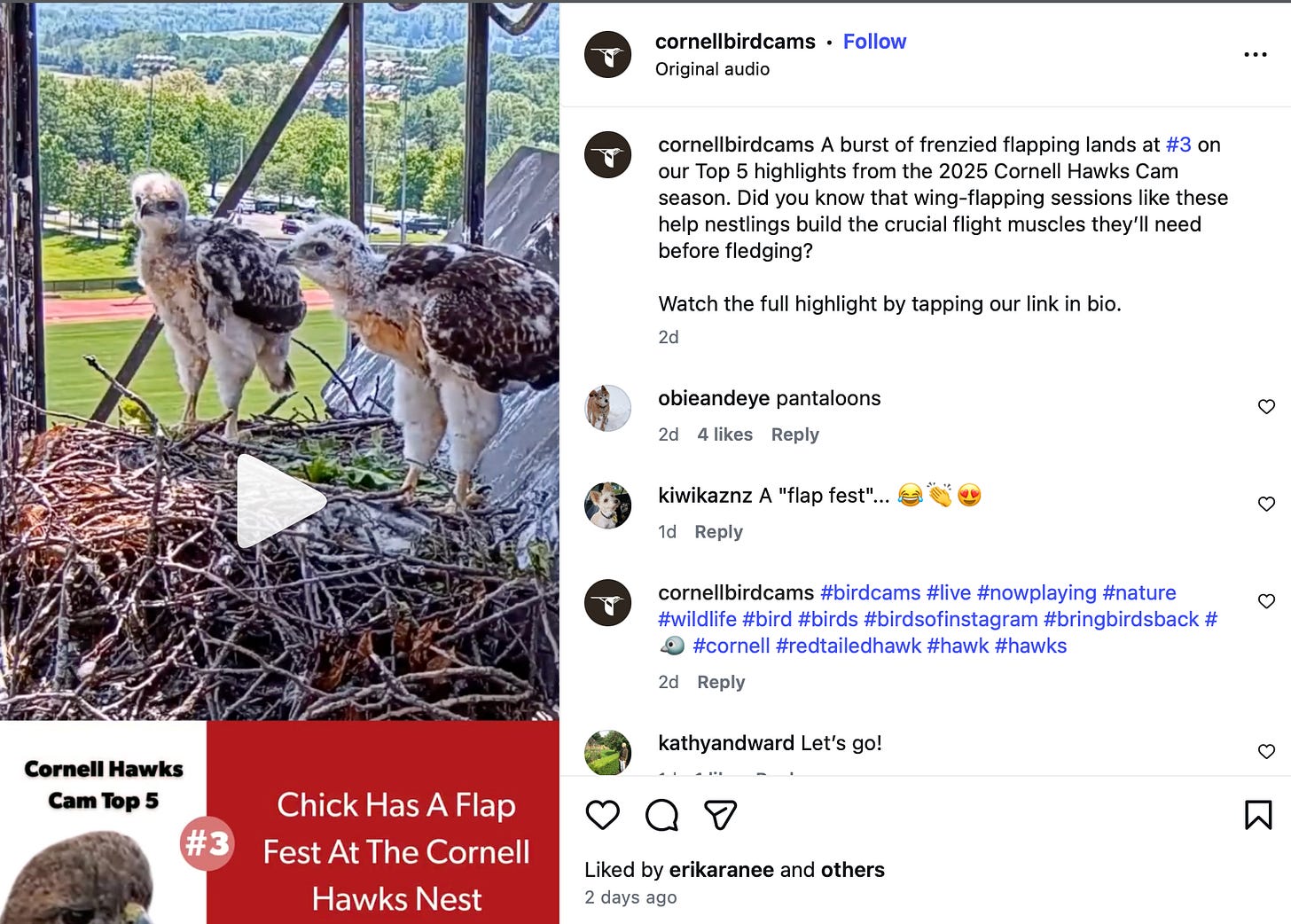

Cornell Live Bird Cam - A burst of frenzied flapping lands at #3 on our Top 5 highlights from the 2025 Cornell Hawks Cam season.

Go Birding!

Fantastic roundup covering so much ground. The Arizona Bald Eagle migration research (item 2) really caught my attention because it flips our assumptions about seasonal movement patterns. The fact that young eagles head north instead of south challenges the textbook model most people carry around. I worked on a raptor survey in Oregon and we noticed similar counterintuitive behavor with certain populations but never had tracking data to confirm it.